Professional Associations

Harrington (see reference below) asserts that the desire to preserve the past is not a modern phenomenon. However, by the 20th century, the time had come for the internationalisation of heritage concerns and practices. This was facilitated by the impacts of globalisation and the communication revolution. The impetus for a global program of heritage protection arose in response to the recognition of the potential for destruction that followed World War II, and within the framework of emerging national identities and policies during the 1960s and 1970s.

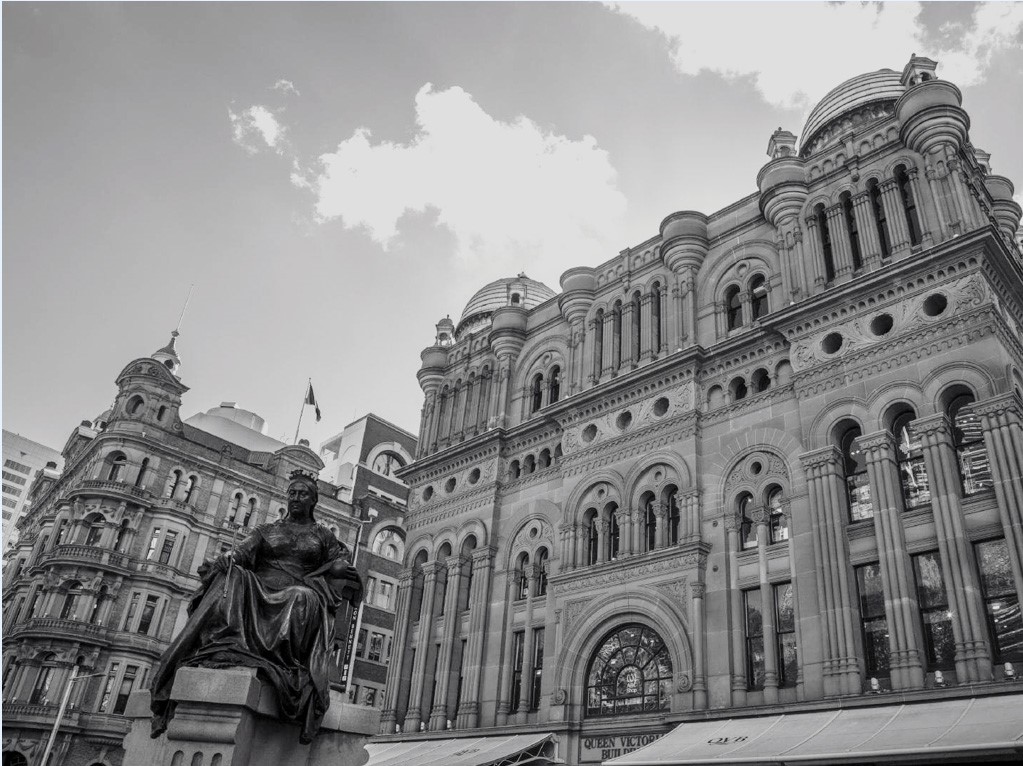

Fig 1 – Cronulla Beach – NSW, Australia

Harrington maintains that this period saw a growth in interest in natural and cultural heritage, and in the past, in both a group and individual sense. This interest was often vocalised through community concerns, albeit more commonly in Western nations. However, the drafting of national legislation and conservation policies was dominated by the views of professionals involved with the identification and protection of heritage. At this stage, these were predominantly Western-educated natural scientists, archaeologists, architects and historians.

It was the input of practitioners from such disciplines that generally informed the policies of heritage management systems and continues to do so. These specific disciplines lie outside areas that are making the greatest contributions to understandings of community identity and attachments: for example, human geography and anthropology. The ongoing involvement of what is effectively a restrictive arena of interest has supported a positivist approach to heritage management that reinforces a particular view of cultural and natural heritage that is tied to objectivism provides additional insight into the disciplinary conundrum:

Maintaining the correct balance between the requirements of sites and of the people who have placed their stamp on nature … is a delicate ‘balancing act’, calling for skills and expertise and experience that, with due respect, is seldom found in our genre.

Harrington reminds us that many of us in heritage management positions were never recruited on the basis of the above qualities … “certainly it was never our vocation to put people as part of the landscape because what we always put to the fore is the ‘object’, ‘artefact’, ‘archaeology’, ‘specimen”.

To a great extent, the globalising approach was enshrined following the Venice UNESCO resolution adopted in May 1964, which established an international non-government organisation for monuments and sites: ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites). Following the ratification of the resolution by 25 countries in 1965, ICOMOS was officially founded in Warsaw.

In 1966 ICOMOS adopted the Venice Charter, the International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Site, as its fundamental ethical guideline, reinforcing the construction of cultural heritage as monuments and sites, in line with contemporaneous discussions by UNESCO in the context of ‘monuments of world interest’. ICOMOS was a major contributor to the development of the World Heritage Convention, and under Article 8(3) of that convention is established as an advisory body to the World Heritage Committee, together with the IUCN and ICROM.

Thus, we continue to perpetuate strictly western views of cultural built heritage in an increasingly globalised world. Somewhere down the line, this dichotomy will need to be resolved.

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21

26 February 2018

Reference:

Harrington, JT, Being Here’: Heritage, Belonging and Place Making, SCIENCE VERSUS ‘SENSE’

The Evolution of Heritage Discourse, 2004, https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/71/3/03chapter2.pdf

Related Articles

Five things you need to know about cultural built heritage

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage, Gentrification, Urbanisation & Tourism

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage is indicative of truths as they emerge from contemporary practice

How often is it said that we view the past through our own eyes. Here we are in 2018 viewing…

Read more

Is Heritage Chauvinistic?

David Lowenthal writes that heritage betokens interest in manifold legacies – family history, familiar landmarks, historic buildings, art and antiques,…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.