Professional Associations

What is an historic urban landscape of HUL as it is known in its abbreviated form? The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Initiative was launched in 2005 to raise awareness of the need to safeguard historic cities by including inherited values and cultural significance of their wider context into strategies of conservation and urban development. It had become apparent that protection and conservation of living historic cities by way of ‘conservation areas’ or otherwise geographically limited ‘special districts’ was no longer sufficient to cope with the increasing pressures exerted on them (Bandarin, 2010).

The HUL Initiative emerged from the international conference, World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture – Managing the Historic Urban Landscape, held in Vienna (Austria) in May 2005, which issued the ‘Vienna Memorandum’. The Vienna Memorandum, developed with the cooperation of the World Heritage Centre’s partner organisations in this initiative, was an important starting point for rethinking urban conservation principles and paradigms, which have been the subject of a series of international expert meetings organized by UNESCO (Bandarin, 2010).

All these efforts are focused on the development of a new international standard-setting instrument for the safeguarding of historic urban landscapes, scheduled for adoption by UNESCO’s General Conference in 2011. HUL is an updated tool for urban conservation much needed to facilitate the proper protection and management of living historic cities: not only those inscribed on the World Heritage List but also those that have national, regional and local importance/ significance.

Fig 1 – Historic Urban Landscape, Hong Kong

The HUL initiative recognises that there are present, imminent and accelerating threats to cultural built heritage in cities. The threats include but are not limited to;

- Diminished funding for preservation at the federal and state levels.

- The impact of transportation projects on cultural resources.

- Legislative enactments designed to pre-empt state and local preservation laws.

- The private property rights movement and its attack on preservation programs at the local level.

- Development resulting in either demolition or retention only of building facades.

- Ignorance of archaeological resources.

- Subordination of historic preservation to other design concerns and agendas.

Fig 2 – Historic Urban Landscape, Hong Kong

Repeated cutbacks in Federal funding and reduced tax incentives combined with a lack of understanding concerning the economic benefits of conservation have sapped valuable energy from the conservation movement. At the same time, planners have a tremendous opportunity to capitalize on positive developments that are building the constituency for conservation, including:

- A greater role for conservation in urban revitalisation, economic development and finance initiatives driven by the private sector.

- An increased commitment to the principle of adaptive reuse, ensuring that architectural and historic resources are economically viable contributors to their communities.

- Growing cooperation between professional disciplines, community groups, and their organisations to promote effective preservation strategies at the national, state, and local level.

- Increased availability of environmental laws and programs as a resource.

- Emerging conservation strategies that address and interpret the histories and cultural legacy of all segments in society without regard to ethnicity, religion, or social strata.

- Growing use of conservation tools as a means to accomplish other desirable objectives such as more compact communities, neighbourhood conservation and cohesion, economic development and tourism.

- Greater programming of public transport funds for enhancements that build on the foundations of neighbourhood conservation and conservation planning.

- Greater use of tax benefits to promote conservation of communities.

Fig 3 – Historic Urban Landscape, Hong Kong

The above list of enhancements is drawn from the ‘Policy Guide on Historic and Cultural Resources’ – Copyright 2007, American Planning Association. The APA policy guidelines support funding of programs for the conservation of historic resources at all levels of government. The components of the program include:

- an ongoing survey and evaluation process;

- protective legislation, expressed in clear and reasonable standards and based on qualified expert opinion or acknowledged resources in the field;

- financial incentives to encourage rehabilitation and restoration;

- historic conservation plan development;

- adequate budget allocations for qualified staff in public agencies;

- cooperative educational efforts with the private sector and citizen groups;

- interdisciplinary participation and alliances of planners with other professionals in fields related to historic conservation;

- coordination of conservation initiatives with education, citizen participation, history, public art, and other programs;

- implementation strategies capable of protecting, enhancing, and extending the benefit of cultural resources for future generations;

- provisions (in the form of ordinance or policy) to secure temporary delays to the alteration or demolition of designated cultural resources until their preservation or protection may be fully explored;

- adaptive reuse policies supported by tax or other incentives.

In accordance with the above guidelines, it is hoped that eventually, Australia will adopt the HUL principles. It has already been adopted in Ballarat, Victoria, but a wider and more comprehensive system ought to grow into a robust management strategy for the protection of our heritage assets at the local, state and national level.

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21 – 1 August 2016

References:

1. Bandarin, F. (2010) – Managing Historic Cities World Heritage Centre, UNESCO

2. Policy Guide on Historic and Cultural Resources (2007) – American Planning Association

Related Articles

9 Types of Heritage Building

Since colonial times in NSW, Australia, there are nine distinct styles of European, English and American inspired heritage architecture. Listed…

Read more

A recent visit to the UK town of Bury St Edmunds

In February, this year (2017), I travelled to the quaint English town in Suffolk (East Anglia) known as Bury St…

Read more

Heritage Movement – USA

In discussing the early days of the heritage movement in America, Rhonda Sincavage posts on the Public History Commons website…

Read more

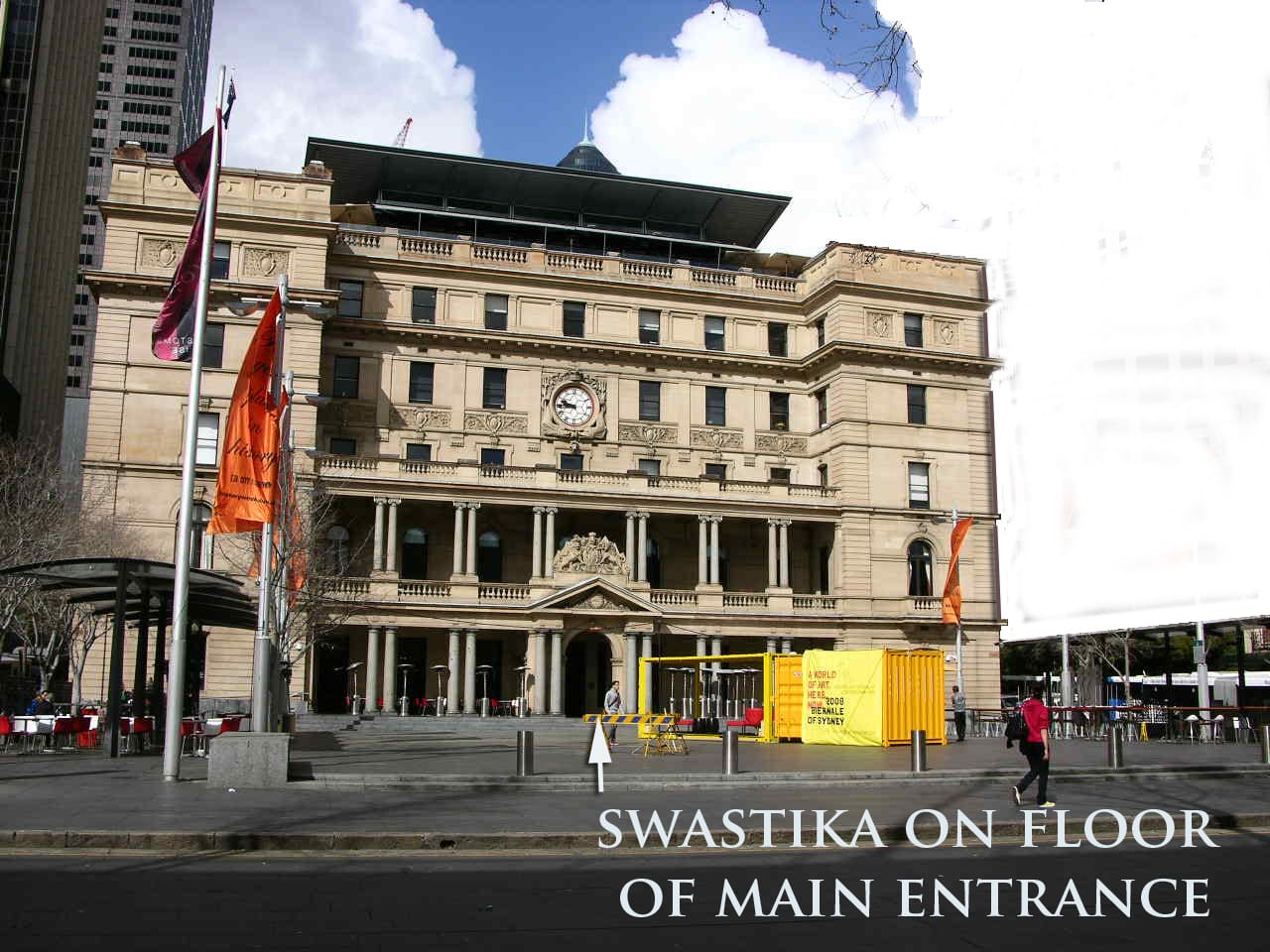

Contested Significance at Customs House

Customs House is an elegant sandstone building at Sydney’s busy Circular Quay, built in stages between 1845 and 1917, and…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.