Professional Associations

In February, this year (2017), I travelled to the quaint English town in Suffolk (East Anglia) known as Bury St Edmunds. It has an interesting history which I set down below from Tim Lambert’s brief history of the town. Its recorded history is some 1500 years in the making.

Bury St Edmunds began as an Anglo-Saxon settlement. In 630 Sigeberht the king of East Anglia founded a monastery there. In the 9th century Edmund was king of East Anglia. He was martyred in 869 and at the beginning of the 10th century, his remains were brought to the monastery for safekeeping. In the early 11th century King Canute replaced the monastery with an abbey. The abbey soon became rich and powerful.

Fig 1. General street scene in the town of Bury St Edmunds

In the late 11th century, Bury St Edmunds grew into an important town. This was partly due to Abbot Baldwin who encouraged craftsmen to come to the town and laid out new streets. By the 12th century, Bury St Edmunds probably had a population of about 4,000. In the Middle Ages, many people went to Bury St Edmunds to visit the remains of St Edmund. In those days, it was common for people to go on pilgrimages to visit the shrines of saints. Naturally the townspeople benefited from visitors spending money in the town – the very origins of tourism today.

In 1214 the English barons met at Bury St Edmunds. They swore an oath in the abbey to force the king to accept Magna Carta. This gave rise to the town motto: ‘Shrine of a king, Cradle of the law’. Medieval Bury St Edmunds was a wool-manufacturing town. In Bury, wool was woven and fulled. That means the wool was pounded in a mixture of clay and water to clean and thicken it. Wooden hammers worked by watermills pounded the wool. In addition, there were craftsmen typical of medieval towns such as skinners, shoemakers, butchers, bakers and brewers. Bury St Edmunds was also an important market town. In the Middle Ages, fairs were like markets but they were held only once a year and they attracted merchants from a wide area.

In the Middle Ages, Bury St Edmunds was controlled by the Abbot who was much resented by the townspeople. Matters came to a head in 1327 when the people rebelled. However, the Abbot retained control of the town. The Abbey itself was destroyed by fire in 1465, but it was rebuilt.

Fig 2. General street scene in the town of Bury St Edmunds

In the Middle Ages, churches operated as hospitals. There were several in Bury St Edmunds where monks looked after the poor and the sick. Like all English country towns, Bury St Edmunds was devastated by the Black Death of 1349 which may have killed half the town’s population. However, Bury soon recovered as later on, there were people from the countryside looking for jobs in the towns.

In 1608 Bury St Edmunds suffered a severe fire which destroyed 160 houses. Like all towns in those days, Bury St Edmunds suffered outbreaks of the plague. It struck in 1589 and 1637. A by-law was passed in 1607 forbidding people to let pigs roam the streets. In the 16th century the cloth industry in Bury St Edmunds continued to flourish. However it declined in the 17th century. By the early 17th century Bury probably had a population of about 5,000 but it was losing its importance. By the 18th century it had dwindled to being a quiet market town.

Daniel Defoe said in the 1720s referring to Bury; ‘There is no manufacturing in this town, or very little, except spinning. The chief trade of this place depends upon the gentry who live there or near it’. i.e. trade depended on the gentry spending money in the town.

Bury St Edmunds continued to develop in the 18th century. The Unitarian Meeting House was built circa 1711-1712. Angel Corner was also built in the early 18th century. The building called the Athenaeum was built early in the 18th century as Assembly Rooms where people could play cards and attend balls. It became the Athenaeum in 1854. Meanwhile Market Cross was built in 1780. It was designed by Robert Adam.

In 1801 Bury St Edmunds had a population of 7,665. By 1900 it had a population of about 16,000. However, the population of Britain quadrupled during the same period from about 9 million to about 37 million. So relatively Bury St Edmunds declined. In the 19th century Bury St Edmunds remained a market town. The only significant industry was brewing. In 1871 the fair of St Matthew, one of two in Bury St Edmunds, closed.

However, conditions in the town improved. In 1811 an Act of Parliament formed a body of men to pave, clean and light the streets (with oil lamps).

Fig 3. Angel Hill in the town of Bury St Edmunds

Theatre Royal was built in 1819. The first modern hospital in Bury St Edmunds was built in 1826. A gasworks was built in Bury in 1834 to provide gas for lighting. Bury gained its first police force in 1836. The town was connected to Ipswich by railway in 1846 and to Cambridge in 1854. From the 1860s, a piped water supply was created. A sewage works was built in 1885. The Corn Exchange, where grain was bought and sold was built in 1862 and Bury St Edmunds Borough Museum opened in 1899.

The Church of St Edmund was built in 1837 and the Church of St John the Evangelist was built in 1840. The first council houses in Bury were built in the 1920s. Priors estate was built in the 1930s. More council houses were built after 1945, some of them to replace demolished slums. Many private houses were also built such as Moreton Hall estate in the 1980s and 1990s.

A sugar beet factory was built in Bury St Edmunds in 1925. From the 1950s industrial estates were built in Bury St Edmunds to attract new industries. However, brewing is still a thriving industry in Bury St Edmunds.

Reference: A BRIEF HISTORY OF BURY ST EDMUNDS by Tim Lambert – http://www.localhistories.org/burysteds.html

Paul Rappoport CEO

Heritage 21

14 March 2017

Related Articles

9 Types of Heritage Building

Since colonial times in NSW, Australia, there are nine distinct styles of European, English and American inspired heritage architecture. Listed…

Read more

Historic Urban Landscapes (Part 1)

What is an historic urban landscape of HUL as it is known in its abbreviated form?

Read more

Heritage Movement – USA

In discussing the early days of the heritage movement in America, Rhonda Sincavage posts on the Public History Commons website…

Read more

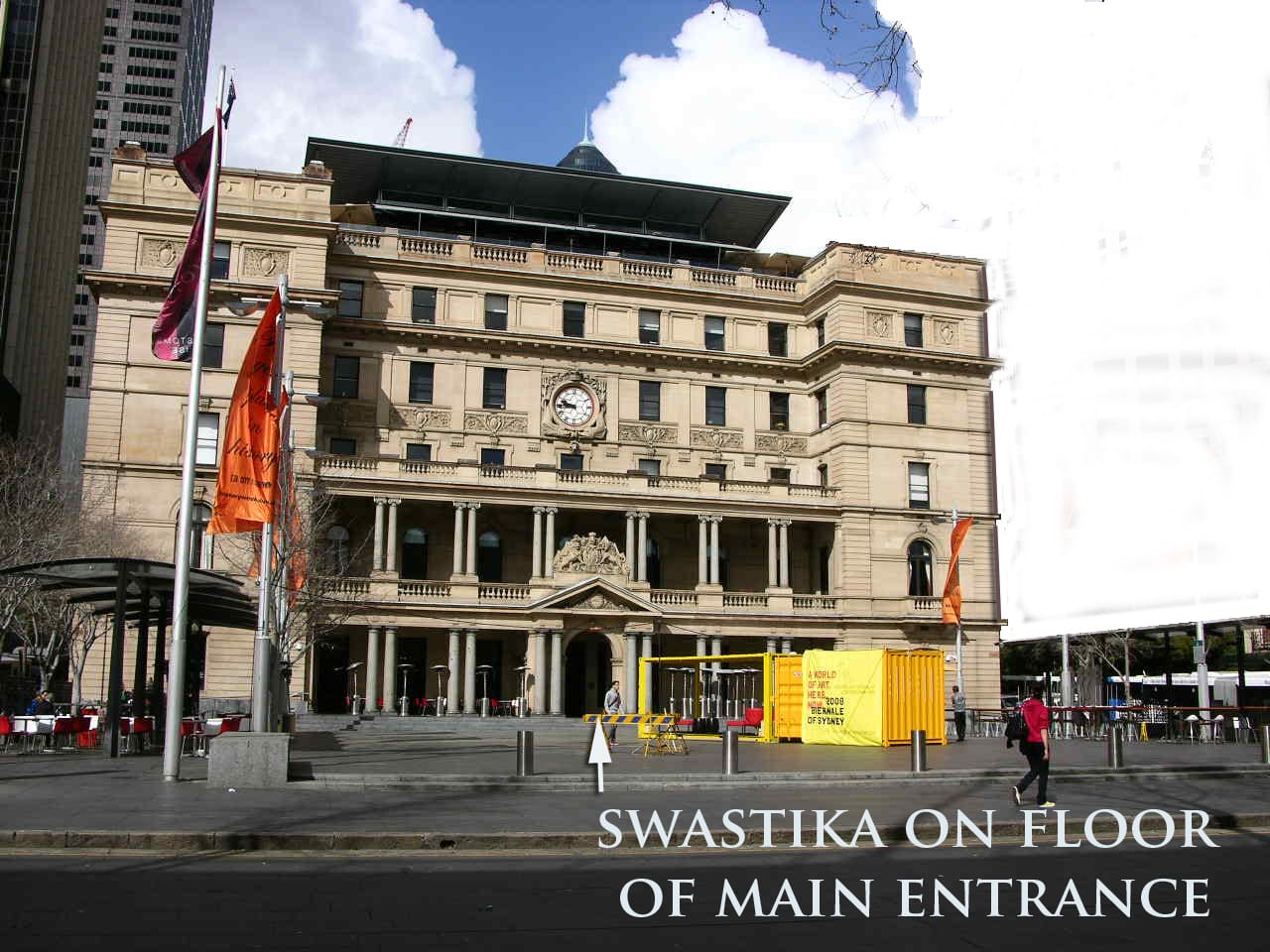

Contested Significance at Customs House

Customs House is an elegant sandstone building at Sydney’s busy Circular Quay, built in stages between 1845 and 1917, and…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.