Professional Associations

As highlighted by OWHC, Council of Europe and EUROCITIES advocates the involvement of communities as an important approach to the conservation, management and promotion of urban heritage. OWHC calls for the provision of oppor¬tunities of engagement and cooperation with and for local communities; having the understanding that urban heritage can act as enabler of sustain¬able development by providing direct and indirect benefits to the daily lives of the cities’ inhabitants. The urban heritage assets can be a resource for the local development of the communities – to be mobilised for and by them. Cultural built heritage is meaningful to society and will gain the support and buy-in of the communities for its proper safeguarding and use.

By engaging communities in decision-making, heritage in this way can also be a fundamental component of human rights of democratic societies’ development, a driver for change, transformation and innovation, not only in the management and governance of the urban heritage and their institutions, but also for the gearing of cultural heritage institutions towards a more participatory culture through the introduction of innovative approaches to the governance of heritage – including co-creation in order to increase the ownership of heritage-led development processes among citizens.

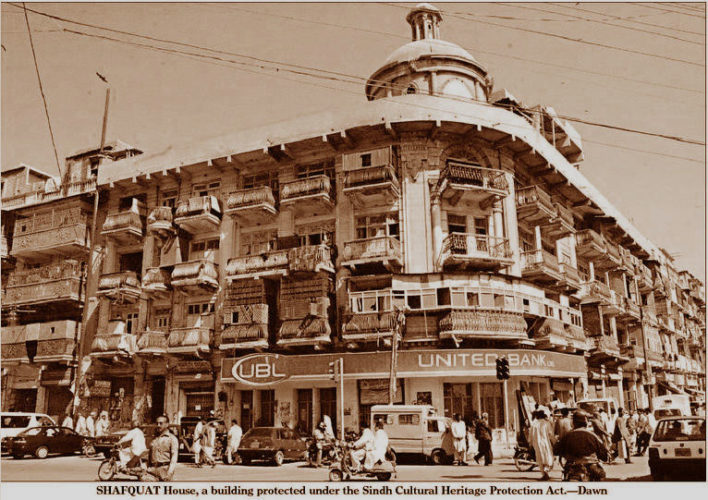

Fig 1 – A Heritage building in Karachi – Pakistan

The “Operational Guidelines for the Implementa¬tion of the World Heritage Convention” (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2016: http://whc.unesco. org/en/guidelines/) emphasises that State Parties to the Convention are encouraged to ensure the participation of a wide variety of stakeholders, including site managers, local and regional governments, local communities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other interested parties and partners in the identification, nomination and protection of World Heritage properties.

The guidelines call for nominations for listing to be prepared in collaboration with and the full approval of local communities. It is important to underline a fundamental principle of UNESCO to the effect that the cultural heritage of each is the cultural heritage of all. Responsibility for cultural heritage and the management of it belongs, in the first place, to the cultural commu¬nity that has generated it and subsequently to that which cares for it.

In the World Heritage Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (World Heritage Committee, 1995, WHC- 95/CONF.203/16: http://whc.unesco.org/en/ses¬sions/19COM) it is stated that participation of local people in the nomination process is essential to make them feel a shared responsibility with the State Party in the maintenance of the site. The Burra Charta (ICOMOS Australia 1999), Article 12 states that conservation, interpretation and management of a place should provide for the participation of people for whom the place has special associations and meanings, or who have social, spiritual or other cultural responsibilities for the place.

As community involvement in urban heritage becomes more and more relevant in conservation, management and promotion of heritage in the world, it is important to develop a common understanding of what community involvement in urban heritage is about and what it is aiming at.

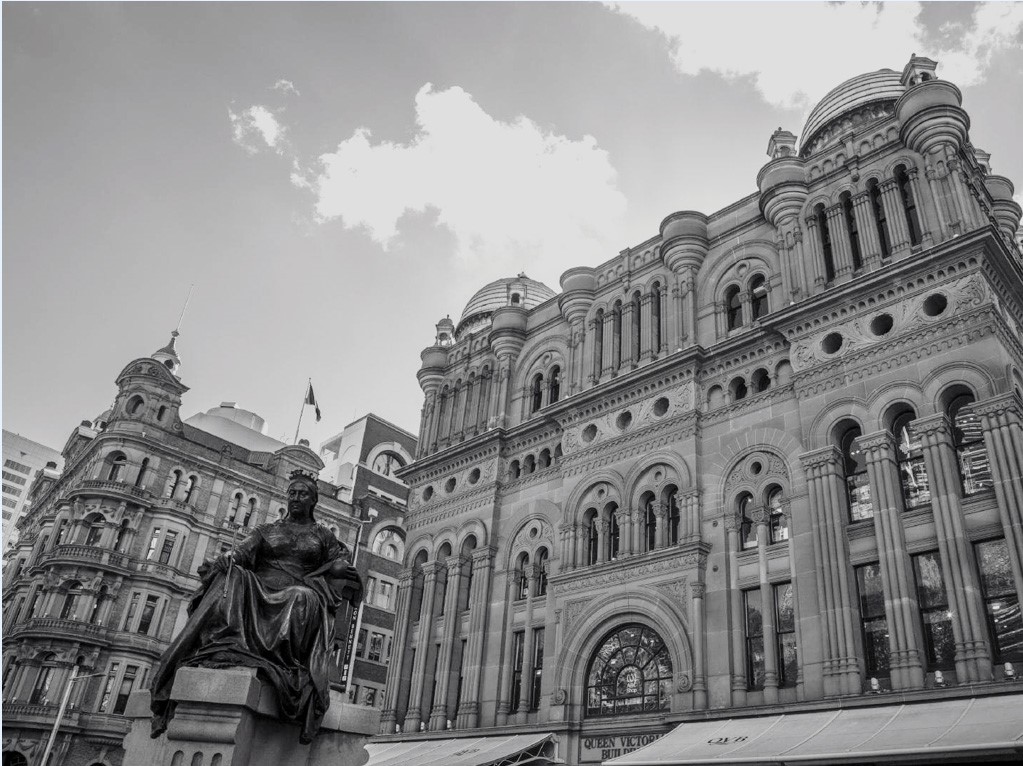

Fig 2 – A Heritage building in Barcelona by Gaudi – Spain

On the one hand to be able to communicate and to exchange within it and on the other hand, to be able to apply this approach for the safeguarding of the urban heritage and for the benefit of the local communities.

Community involvement in urban heritage is about involving, including and the common acting of people, institutions and organisations that are interested in the urban heritage, affected by the urban heritage or live within or close by to the urban heritage.

In the conservation, management and promotion of urban heritage and its beneficial use for the local communities, the people that are interested belong to the so- called heritage community. They feel positive about the urban heritage and can and want to act as supporters. Also, people of the geographical and cultural communities (residents, users, owners, tourists, etc.) can be part of the heritage community if they positively identify with the urban heritage and want to act as supporters. These are identified as multipliers that reach their communities.

Fig 3 – Musical band in European city square entertaining locals and tourists with heritage buildings in the background

People that are affected positively or negatively, may be residents whose daily life is connected to the urban heritage. It may be users (i.e. tourists, people that work, do business in the urban heritage), owners of the urban heritage and people for whom the urban heritage is part of their culture i.e. a church in which they belong and where they meet.

People that live within or close by the urban heritage are the residents irrespective of whether they feel attached or not to the urban heritage or are affected by it provide material study for ascertaining their relation to the urban heritage and what they think or know about it.

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21

26 February 2018

Reference:

Scheffler, N (2017), Community involvement in Urban Heritage, OWHC Guidebook in cooperation with Joint Project European Union / Council of Europe COMUS and EUROCITIES for the OWHC Regional Secretariat Northwest Europe and North America, Monika Göttler & Matthias Ripp.

Related Articles

Five things you need to know about cultural built heritage

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage, Gentrification, Urbanisation & Tourism

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage is indicative of truths as they emerge from contemporary practice

How often is it said that we view the past through our own eyes. Here we are in 2018 viewing…

Read more

Is Heritage Chauvinistic?

David Lowenthal writes that heritage betokens interest in manifold legacies – family history, familiar landmarks, historic buildings, art and antiques,…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.