Professional Associations

There is a ‘perennial divide between heritage conservers and commercial interests. Development proposals; in particular, perhaps, those in the centre of our towns and cities where development land is usually scarce and therefore expensive, frequently bring this issue into sharp focus. On the one hand, conservationists fight to protect and preserve what they perceive to be priceless historic assets which, they contend, often serve both to preserve important elements of local or national history and culture and also to provide a community focus through the preservation of what has come to be termed ‘collective memory’. On the other hand, developers and property owners seek to maximise the commercial worth of their investment. Although the balance which is struck between these potentially opposing views tends to shift over time as society’s values ebb and flow. Compare the present vogue for the adaptive reuse of historic buildings with the wholesale demolition resulting from the ‘brave new world’ approach espoused by the town centre developers of the 1970s’. (ref 5)

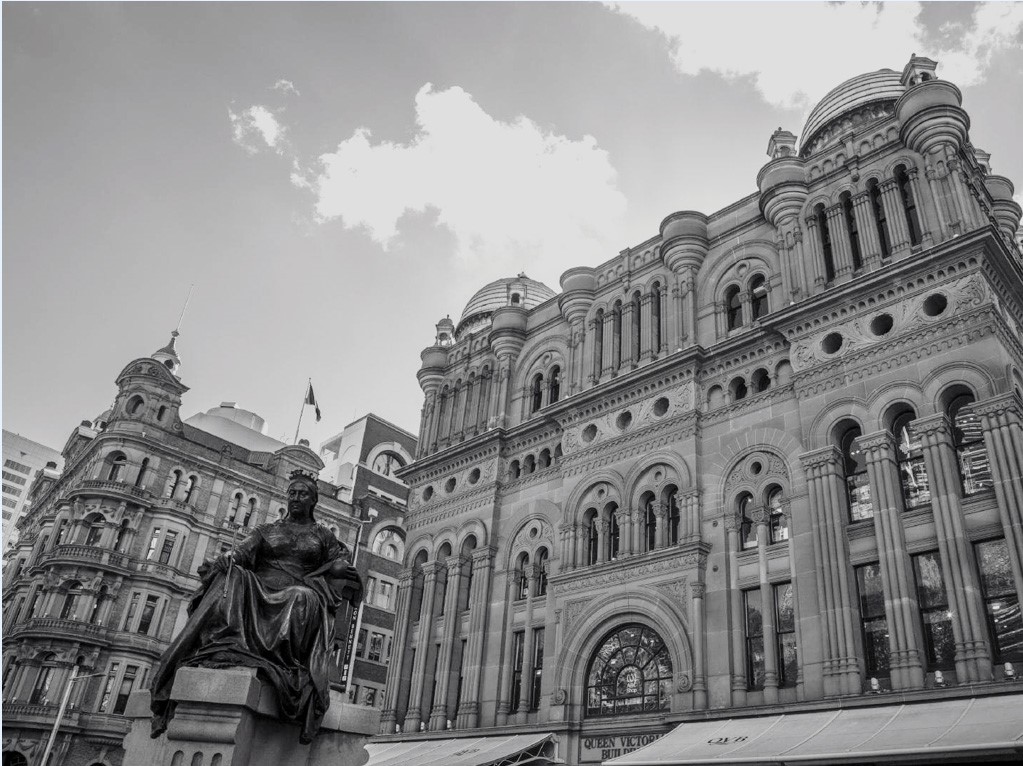

Our heritage is rich and diverse and it includes buildings, monuments, gardens, cemeteries, landscapes, shipwrecks archaeological sites and other places and objects. The heritage places and objects included in heritage registers contribute to the attractiveness and liveability of our cities, towns and regions. They provide a broad range of economic, social and environmental benefits. Heritage listing and heritage protection is ultimately a ‘public good’ driven by the broader community (Ref 2), but what precisely, are the benefits?

A recent publication (2017) entitled; ‘Heritage Regulations – Regulatory Impact Statement’ issued by the Victorian State Government in Australia, sets out the benefits of heritage as follows;

Economic benefits

Heritage is one of the most rapidly expanding tourism segments in terms of visitor numbers globally and is a major attraction for our cities and regions. Studies have shown that ‘cultural tourists’,[1] which include those visiting historic and heritage places, tend to stay for longer and spend more than ‘non-cultural tourists’. Research undertaken in the United Kingdom also finds that investment in historic visitor attractions provided a range of benefits to the local community by attracting visitors to an area and spending money in local hotels, pubs, shops and restaurants as well as generating employment in the heritage sector and related fields (Ref 2).

A recent study (Ref 2) shows that heritage contributes to economic / business activity in local areas in five different ways: (a) the impact associated with the day-to-day operations of a heritage attraction / facility; (b) the economic benefits associated with heritage-based recreation and tourism; (c) the impact associated with capital works, including restoration and repair / maintenance; (d) how heritage and cultural institutions make a place more attractive for non-tourism businesses and workers to locate; and (e) economic security. In the case of research that looks at operational, tourism and restoration/repair, a further variable across reports is their geographic scale of analysis – ranging from impacts at a national scale to the localised impact of single heritage sites and attraction.

Social benefits

Most people consider that the historic houses in their area are an important part of the area’s character and identity. Similarly, the vast majority of people consider heritage to be an important part of Australia’s identity and culture (Ref 2).

Socially, heritage assets have the ability to make contributions to an area’s liveability and identity. In many cases, they are places that are a focus for community activities, such as public halls, schools, mechanics institutes, places of religious worship and parks. Heritage assets also often include local landmarks that people identify with a town or area, such as significant buildings, monuments and bridges (Ref 2).

Heritage conservation projects often also provide social benefits through community involvement and raising the community’s awareness of its heritage. Once completed, heritage conservation projects are often accompanied by community events, further enhancing the community’s sense of identity Ref 2).

Environmental benefits

Conserving buildings rather than demolishing them can also provide a significant reduction in the amount of landfill. Studies have indicated that waste from building demolition makes up nearly 30 per cent of landfill. Environmentally, finding new ways to re-use heritage buildings – rather than erecting new buildings – can have significant savings for the environment Ref 2).

Typically, the amount of embodied energy in a house is equivalent in amount to its energy consumption over 10 years and the amount of embodied energy in an office building equivalent to its energy consumption over 30 years. Heritage buildings also tend to be more energy efficient than new buildings (Ref 2).

‘The benefits of most goods and services, including heritage property, usually accrue to those who own them or pay for them; not to those who use them. In the case of many heritage properties the reverse is true. An area with architectural or heritage significance may benefit those who reside in it, those nearby or those who just pass through or visit it, as in the case of a heritage property or precinct drawing tourists to the area. These indirect benefits can be extremely difficult to measure, are really static and can apply to an area or a single building. Benefits can be dynamic and can be reflected in higher returns in the form of increased overall value and rents. The returns may be greater than the cost of restoration and maintenance. The market however, may view the cost as prohibitive and the end market consumer may not be prepared to meet the rental levels required. This could be said to be true of any property/development situation, but may erroneously appear to be accentuated in the case of heritage properties’ (Ref 4).

The historic environment

According to Values and Benefits of Heritage (Ref 2), heritage sites and buildings are seen as important to local communities. Heritage sites and buildings play an important part in how people view the places they live, how they feel and their quality of life. People are interested in how the built environment looks.

The natural environment

People want to live near green spaces, such as parks and commons. In addition, when asked what makes somewhere a good place to live, respondents to a survey, selected green amenities (e.g. open spaces, trees and greenery) ahead of transport, jobs, housing and local services (Ref 3).

Conclusion

‘The concept of public value appears to be an interesting idea for assessing the worth of cultural heritage, and could also, in the fullness of time, evolve into a useable tool. It is, however, important that, as competition for scarce resources becomes ever more fierce, we are able to quantify the value of heritage in realistic, responsive, easily understandable and robust ways’. (Ref 5)

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21 – 12 July 2017

References;

(Ref 1) Heritage Regulations – Regulatory Impact Statement, Victorian State Government, 2017

(Ref 2) Values and benefits of heritage – A research review compiled by the Heritage Lottery Fund Strategy and Business Development Department, Gareth Maeer , Amelia Robinson, Marie Hobson – April 2016.

(Ref 3) Scottish Centre for Social Research, Scottish Social Attitudes Survey 2009: Sustainable Places and Greenspace, 2010.

(Ref 4) Heritage Australia: A Review of Australian Material Regarding the Economic and Social Benefits of Heritage Property by Peter Wills and Dr. Chris Eves (undated)

(Ref 5) The Value of Built Heritage, College of Estate Management by Adrian Smith, CEM Occasional Paper Series, 2010

Related Articles

Five things you need to know about cultural built heritage

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage, Gentrification, Urbanisation & Tourism

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage is indicative of truths as they emerge from contemporary practice

How often is it said that we view the past through our own eyes. Here we are in 2018 viewing…

Read more

Is Heritage Chauvinistic?

David Lowenthal writes that heritage betokens interest in manifold legacies – family history, familiar landmarks, historic buildings, art and antiques,…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.