Professional Associations

Most countries, regions and states utilise heritage listing as a means of protecting heritage assets, but many of these lists are faulty, omissive, repetitive or incomplete. Quite often, as a cultural heritage advisor, I have come across buildings in conservation areas that are un-listed, yet they possess vary rare and distinctive fabric. Likewise, I come across many buildings that are neither listed nor in conservation areas that should be listed but are blatantly not. Who keeps tabs on this and who decides to list buildings in the first place?

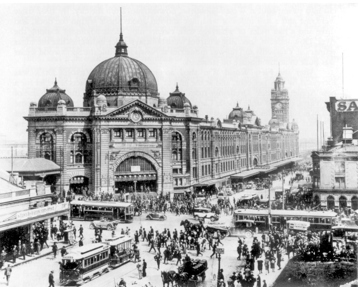

Fig.1 – Heritage buildings in the Paddington Conservation Area in NSW, Australia

In NSW, we have a complex system of cultural heritage listing. Most of the items are locally listed. Some are state-listed; a few are listed on the Commonwealth Heritage Register and even less on the National Heritage Register. In Australia, we have 18 World Heritage listings (UNESCO); three of which are buildings and places – the rest being of natural heritage significance. Apart from individually listed heritage items, we also have conservation areas that may either be state listed (Braidwood, NSW) or locally listed (Paddington, NSW).

To get a building locally listed, the council usually appoints a heritage property consultant to undertake a cultural heritage assessment in which the consultant goes about the designated area identifying buildings and places that may be of cultural heritage significance. The consultant draws up a list and hands it to the council which then advises the consultant which items should or should not be listed. A draft list is drawn up and all affected owners are notified and invited to make submissions back to the council. Invariably, most owners do not want their properties listed because they perceive a devaluation in market value as a result of the restrictions placed upon future development as a result of the listing.

After a long-drawn out process and no doubt a series of vexatious objections on the part of the owners, a final list is drawn up and gazetted. This process could take up to 5 years. The gazettal requires the Local Environment Plan (LEP) to be amended because the heritage list of buildings, places trees and sites as well as conservation areas, form part of the LEP.

Fig.2 – Heritage building in the Braidwood Conservation Area in NSW, Australia

Once an item is on a council heritage list for locally listed items, it is extremely difficult to have that listing removed unless there are extenuating circumstances such accidental demolition, structural collapse or advanced material dilapidation. However, such extenuating circumstances are rare and seldomly persuasive especially when owners attempt to over-emphasise dilapidation as a reason to have the item removed from a list.

In my experience as a heritage property consultant and conservation architect over the last 30 years, I have come to realise that councils are highly protective of their listed items and therefore generally opposed to attempts by owners to have items removed from lists. Similarly, the local communities are generally highly supportive of local council heritage lists. Yet, I have noticed over the last 15 years that the pace of heritage listing has slowed down and many local council lists have become stagnant i.e. not many new items are added to the lists as they become identified by local constituents, community groups (such as DOCOMOMO), professional associations (such as the Australian Institute of Architects), NGOs (such as the National Trust), historical societies, owners or government.

De-listing, although often attempted, is rare in NSW and when attempted, invariably gets knocked back by councils under internal review processes. By contrast, when an omission on a list has been brought to the attention of a NSW council by a constituent, rate payer, professional association or the National Trust, the council may utilise a reserve power by retro-actively listing items under their special powers by placing an interim heritage order (IHO) on a previously un-listed building or place.

I find IHOs divisive and unnecessary not to mention the extremely negative effect they have upon an owner or developer in regard to development applications which may already be on foot. There is a better system adopted in the UK whereby local councils are required to regularly assess their lists (say on a 5-year basis) and to add new items proactively. Proactive listing avoids vexatious responses by owners and developers to IHOs which invariably involve hostile community approaches to random designation of cultural heritage significance within a suburb or an urban main street context.

Fig.3 – Shop Houses in Hong Kong which are not protected and should be placed on cultural heritage lists

Besides, cultural heritage significance or the attribution thereof continually shifts and unless heritage lists are updated, renewed and augmented, they become stagnant and largely meaningless.

The notion that significance shifts and changes in society is, in my opinion, insufficiently recognised. Certainly, in Australia, while the notion is appreciated in academic circles, it is not practically applied. Hence, we have heritage lists which are outdated, concentrated by way of building type and lacking in terms of the zeitgeist.

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21

31 May 2018

Related Articles

Heritage Disconnect

Dr. Robyn Clinch (see reference below) writes that there is a considerable disconnect between the theoretical education of potential heritage…

Read more

Heritage Significance on the Cusp

What is heritage significance. Is the Sydney Opera House significant?

Read more

Heritage-Tourism – Loving it to Death

How often have we all heard or read the phrase; “Tourism is a driver of economic development”.

Read more

What are the present day concerns with cultural heritage?

Heritage – alienation from the means of production? Many years ago, Karl Max and Friedrich Engels coined the phrase; ‘alienation…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.