Professional Associations

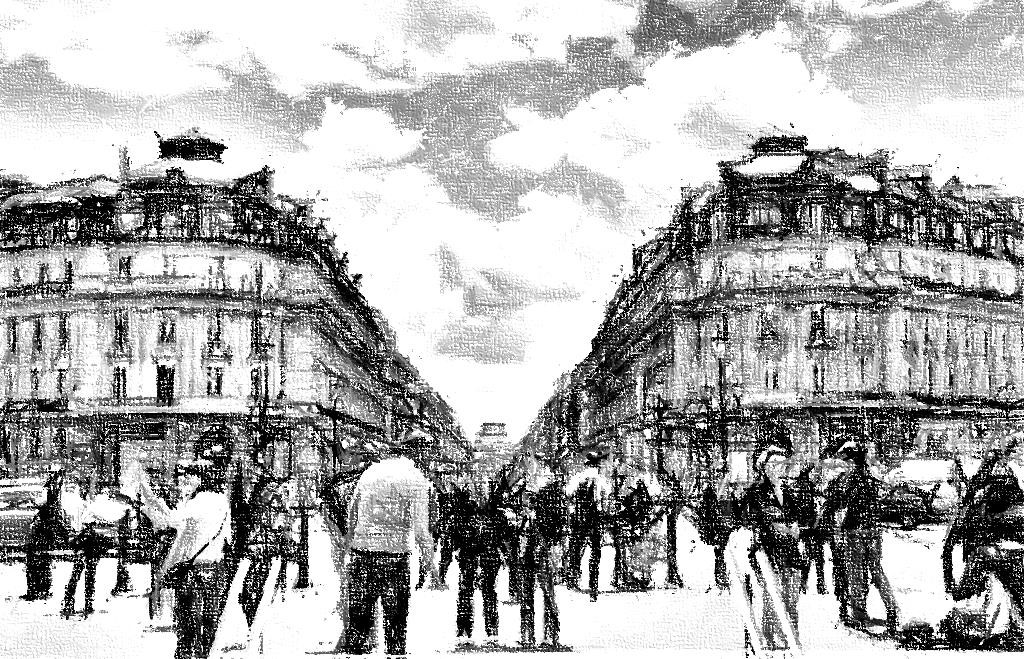

Fig 1 – Demolished heritage item in the foreground – Liverpool (NSW) Australia

Who makes decisions about heritage at federal, state and local government level?And who in the private sector makes decisions about heritage? Is cultural built heritage properly presided over by professionals? If so, how tendentious are they? What are their qualifications? And, in the community, what personal agendas are prone to render a decision biased or subjective?

This is a very difficult topic. There often appears little basis for one or another party/ group/ panel/ council/ Court to formulate an opinion based on strict rules or guidelines concerning cultural built heritage precedents, policies, approaches, positions and theories. It is often a case of he or she that shouts loudest who gets heard – irrespective of the merits of their argument.

In Australia, heritage policy, as currently formulated and implemented at the federal, state and local level, often partakes more of high farce than of the rule of law. Decisions concerning cultural built heritage are highly subjective and often executed by plainly unqualified people. The purpose and basis of decision-making in the heritage sector is seldom accurately or candidly portrayed, let alone understood by its vehement zealots. Its diversion to dubious or flatly deplorable constructions and argumentation undermines the credit that it merits when soundly conceived and executed. Its indiscriminate, often quixotic demands by owners, developers and public authorities have a tendency to overwhelm and somewhat confuse legal institutions and communities. Thus, the efficacy of idealistic heritage standards such as the Burra Charter and similar heritage declarations are either ignored or plainly besmirched.

Such a situation frequently compromises the integrity of legislative, administrative and judicial processes related to decision-making in the cultural built heritage sector.

As a concept, heritage is peculiarly fragile and therefore vulnerable to widely differing standpoints and positions not to mention the subjective bias and often narrow focus of its purview. As a set of so-called theoretical principles, it has experienced various incarnations since the 1940s. Yet, howsoever defined, its scope is inherently vague and expansive. Its conventional wisdom as the pursuit of visual beauty and the saving of irreplaceable cultural artefacts, is conceived as an ontological fact rather than a social construct. The former confers an aura of legitimacy which is often exploited by interest groups who believe they have the ultimate say in all matters; ‘heritage’.

There is an emotional response to heritage as well. This renders the pursuit of clear decision-making fuzzy and unsound. Further, the unique concerns of cultural built heritage set it apart from regular land-use planning that is legislated in local and state environmental plans. Often ‘zoning’ ignores heritage assets and listed properties get caught up in zonings which promise development opportunities beyond that which an experienced heritage consultant would deem reasonable and appropriate. This immediately sets the pursuits of planning apart from heritage – the latter constricting every effort possible to retain the intrinsic significance values of the affected item.

The multi-faceted nature of heritage significance as a concept is largely misunderstood and abused. The consequence of heritage being so ill-treated, places enormous stress on clear- decision-making processes in respect of development and conservation – a polarity of opposites that can be likened to warfare among contending groups. Under such contention, inevitably growth outweighs conservation. Development is largely unstoppable save political will. Sadly, governments at all levels in Australia have mostly retreated from the protective standpoints that we knew back in the 1980s and 1990s. The saga moves on.

Controlling the pace and character of environmental change is largely driven by state and federal government agendas. In NSW, population growth has led to the primacy of a housing drive in order to accommodate incoming residents in suburbs and parts of the city that were clearly never built nor contemplated to have to deal with such enormous infrastructure. The results are obvious. Heritage has been surrounded by mega-scaled buildings that make the antecedent structures look plainly ridiculous and out of scale. The process has led to a form of chronic urban expansionism and gentrification and has radically reduced the visual setting and integrity of the heritage items.

Recent trends illustrate that heritage law and policy are frail vessels for achieving better design outcomes. Decision-making in the realm of town planning tends to be based on quantitative values such as height and floor space ratio etc. rather than qualitative metrics such as better design outcomes and improved urban environments.

Decision-making in regard to heritage is highly complex due to conflicting aesthetic, urban, social, economic and land rights issues being involved. There have been various attempts to systematise the process such as in Chapter 16 of the National Planning Policy Framework in England (2018), but at the end of the day, each pre-condition varies according to the site specific nature of the project; who is driving the project and what are their interests, under what legislative realm, the system operates and the knowledge and experience of the decision maker.

The total quantum of variants having a bearing on such decision making, results in widely differing effects and results. There is no streamlined system; nor should there be. What is required though is clear objectives in the planning legislation. Do we want to retain our heritage items and if so, what relative value do we place upon it? This question applies equally to the legislative and administrative arms of government – perhaps right up to the parliament itself. Is there the political will to value and protect cultural built heritage as a public good or has that objective faded into history?

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21

6 November 2018

Related Articles

Incentivising Ownership of Heritage Buildings

In response to the recent enquiry by the government relating to the NSW Heritage Act, I made the following recommendation.…

Read more

Does the NSW Heritage Act Reflect the Expectations of the NSW community?

In the recent NSW Heritage Act inquiry, I submitted a series of recommendations to the government seeking community response in…

Read more

A New Heritage Council for NSW

In the recent NSW Heritage Act inquiry, I submitted a series of recommendations to the government seeking community response in…

Read more

Heritage has become increasingly Litigious, Mysterious and Flaccid

I have been practicing as a heritage architect in NSW for the last 30 years and during that time, I…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.