Professional Associations

The Canada Research Chair in Urban Heritage of UQAM’s School of Management in collaboration with Concordia University and the Center for Oral History and Digital Storytelling will host the Association of Critical Heritage Studies‘ Biennial Conference under the theme “What does heritage change?” – Conference: 6-10 June 2016, Montreal, Canada.

The Canada Research Chair in Urban Heritage of UQAM’s School of Management in collaboration with Concordia University and the Center for Oral History and Digital Storytelling will host the Association of Critical Heritage Studies‘ Biennial Conference under the theme “What does heritage change?” – Conference: 6-10 June 2016, Montreal, Canada.

The conference will examine the issues and the social, territorial, economical or cultural impacts of tangible and intangible heritage. It aims to contribute to the renewal of knowledge and to the improvement of patrimonial practices in communitarian, academic, territorial and political arenas by examining the manifestations, discourses, epistemologies and policies of heritage—as a phenomenon, a symptom, an effect or a catalyst; as a tool of empowerment or leverage; as a physical or intangible restraint in communities, societies, or any material or mental environment.

The sessions target the following themes:

- Uses of heritage and conflicts: political uses (heritage changes politics)

- Uses of heritage and conflicts: economic value (heritage changes economy)

- Heritage-makers : the activist vs the expert, their changing roles (heritage changes people)

- Heritage makers : co-construction and community-based heritage (heritage changes place)

- Notion of heritage : geographical and linguistic processes of transformation (heritage changes itself)

- Notion of heritage : new objects, new manifestations (changes in heritage)

- Between the global and the local : heritage policies (heritage changes local policies)

- Between the global and the local : postcolonial heritage, heritage and mobility (heritage changes local societies)

- Justice, law and right to heritage (heritage changes rights)

- Epistemologies, ontologies, teaching (how we study and teach heritage as an agent of change)

The above list of targeted themes indicates that in today’s discourse, heritage has become a wide ranging field of contested epistemologies and ontologies. It involves politics, economics, professionalism, communities, linguistics, geography, history, contemporaneity, globalism, tourism, territoriality, mobile capital, localism, justice and human rights not to mention teaching, activism, conflict, transformation, custodianship, commodification, land rights, public goods, individual freedoms and patrimony. It is difficult to ascribe consensus to such a mix of far flung ideas and frames of reference. Heritage is a constantly shifting hypothesis within which a myriad of modules operate. There is no single description or particular slant that it can be given. It has many facets and therefore means many things to different people depending upon their frame of reference.

The above list of targeted themes indicates that in today’s discourse, heritage has become a wide ranging field of contested epistemologies and ontologies. It involves politics, economics, professionalism, communities, linguistics, geography, history, contemporaneity, globalism, tourism, territoriality, mobile capital, localism, justice and human rights not to mention teaching, activism, conflict, transformation, custodianship, commodification, land rights, public goods, individual freedoms and patrimony. It is difficult to ascribe consensus to such a mix of far flung ideas and frames of reference. Heritage is a constantly shifting hypothesis within which a myriad of modules operate. There is no single description or particular slant that it can be given. It has many facets and therefore means many things to different people depending upon their frame of reference.

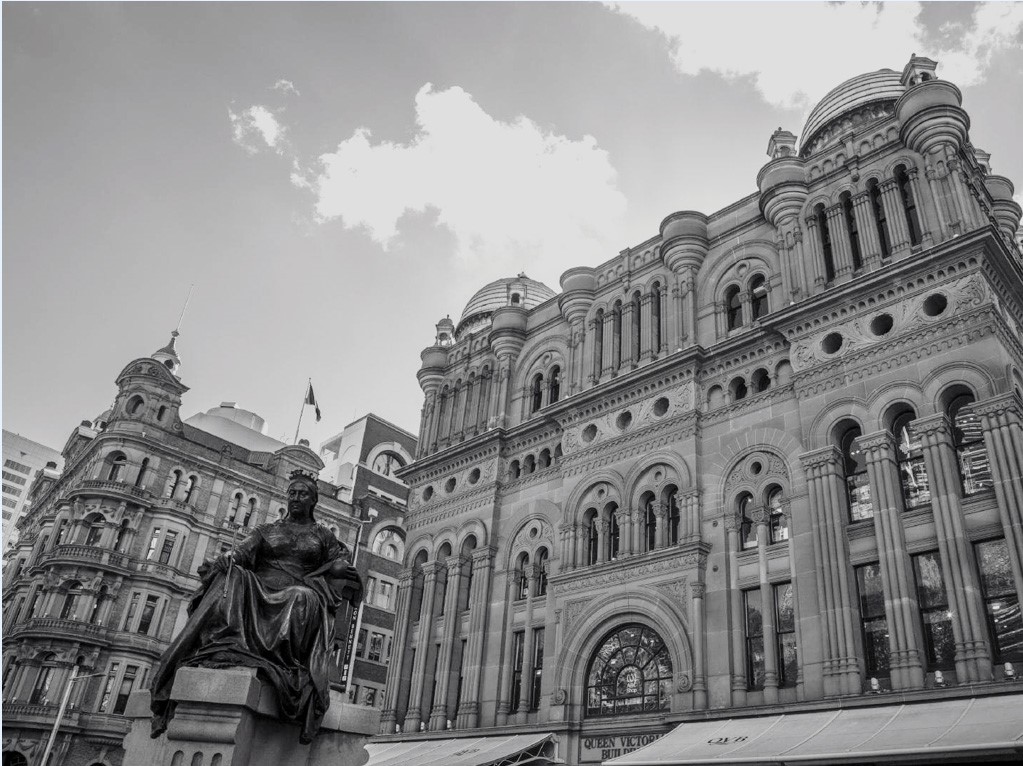

However, above all, it makes sense that heritage needs to be preserved because it comprises an essential link to previous lifestyles and modes of operation. Conserving cultural built heritage reinforces that link and opens up a dialogue with the past. As individuals, we chose our points of departure and our segways in. We do not need to know everything about our built environment. We can respond physically, engage with it socially, delve into the facts and history or simply enjoy the psychological aura that such buildings impart almost on a subliminal spiritual level. This is the reason for tourism to historic towns. It is the reason also for councils to protect conservation areas in their local government areas for purposes of setting up and maintaining a dialogue with the past.

It has often been stated that we are who we were; who our people were and where we came from. The essential historic link is imbued on a personal level; a form of homecoming or connection with our own personal past that is read into the historic environment albeit that we may actually have no prior connection to the place. It is thus personal and generalised; real and abstract. Such pervasive dualism reflects and is reflected in the multi-faceted nature of heritage. The historic built environment is a narrative in whose bricks and stones the story is told; in whose sweep and sway a design intent is communicated albeit through a miasma of historical time. It may not be obvious. Its meaning is inhered in the built fabric and in the form of construction. Its original use is not as important as its fabric because there is a need to recycle old buildings; to repurpose them for contemporary uses. Therein lays the usefulness of conservation.

It has often been stated that we are who we were; who our people were and where we came from. The essential historic link is imbued on a personal level; a form of homecoming or connection with our own personal past that is read into the historic environment albeit that we may actually have no prior connection to the place. It is thus personal and generalised; real and abstract. Such pervasive dualism reflects and is reflected in the multi-faceted nature of heritage. The historic built environment is a narrative in whose bricks and stones the story is told; in whose sweep and sway a design intent is communicated albeit through a miasma of historical time. It may not be obvious. Its meaning is inhered in the built fabric and in the form of construction. Its original use is not as important as its fabric because there is a need to recycle old buildings; to repurpose them for contemporary uses. Therein lays the usefulness of conservation.

If nothing else, heritage changes our attitude by allowing us to enter into a dialogue with the past and visit its historical memory bank. It allows us to read history in the bricks and stones of the buildings as one reads text on a page or notes in a musical score. Each nuanced entry or composition of windows in a facade or the design of a roof and detailed wall element imparts an emotive response suggestive of a wider intrigue/ a bigger scheme/ a higher order of universals and particulars scaled up or down depending on the age, patronage and building technology involved.

Paul Rappoport – Heritage 21 – 3 November 2015

Reference

- Heritage Research Group Bulletin, Cambridge – 19 October 2015

Related Articles

Five things you need to know about cultural built heritage

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage, Gentrification, Urbanisation & Tourism

Historic conservation, writes Regina Bures (see reference below), is frequently associated with gentrification: the incursion of middle-class "gentry" on an…

Read more

Heritage is indicative of truths as they emerge from contemporary practice

How often is it said that we view the past through our own eyes. Here we are in 2018 viewing…

Read more

Is Heritage Chauvinistic?

David Lowenthal writes that heritage betokens interest in manifold legacies – family history, familiar landmarks, historic buildings, art and antiques,…

Read more

Need help getting started?

Check out our guides.

Complete the form below to contact us today.